The North Pole is on thin ice

While the world’s political leaders have left the negotiating table again without an agreement to reduce greenhouse gases, the Arctic has greater problems than ever – 75 percent of the sea ice has disappeared.

“There’s been enormous focus on when the North Pole will be free of ice for the first time, but people have overlooked the great change that has already taken place,” says Professor Jean-Claude Gascard of the Pierre et Marie Curie University in Paris. “Most of the ice at the North Pole has actually disappeared.”

Gascard says that between 50 and 75 percent of the Arctic sea ice around the North Pole has already disappeared – a figure that surprises most people.

Not only has the extent of the sea ice fallen, but the Arctic ice cap has also become two to three metres thinner.

The professor is part of the large European research project Arctic Tipping Points (ATP), which aims at understanding climate change in the Arctic.

The ATP project combines biological data and mathematical models in order to predict how climate change impacts on the Arctic ecosystem.

Cold night gives 20cm of ice

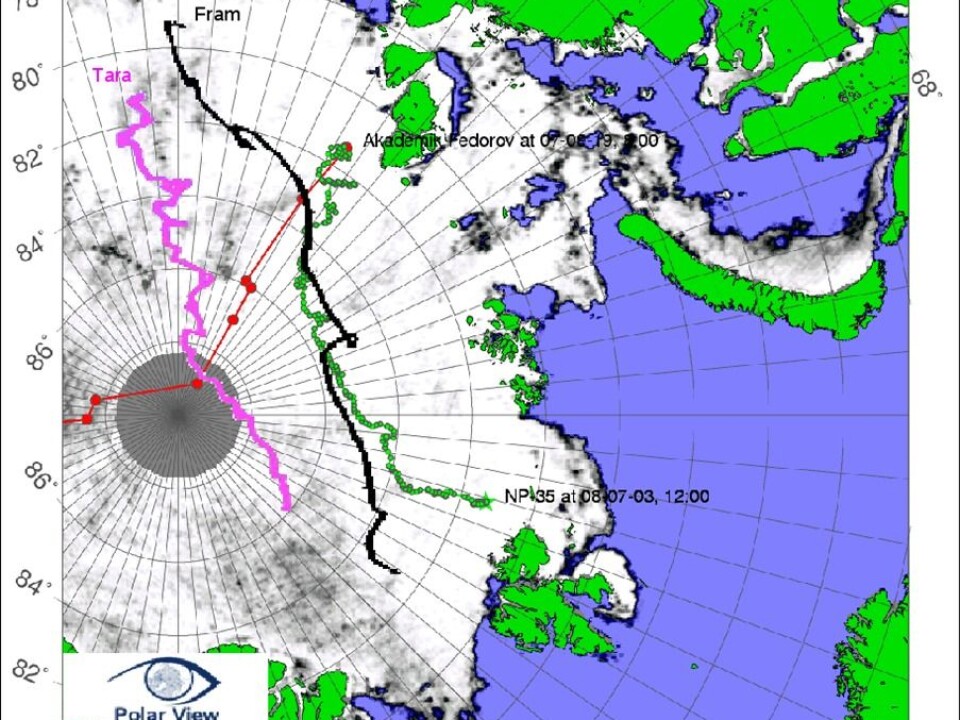

In 2008, Gascard led a research project that deliberately let the expedition ship Tara freeze in in the North Pole’s ice mass. For a year, Tara was borne across the Arctic by the movements of the ice, and it became a drifting home – in the middle of a sea of ice – to a group of researchers.

Every day, to the accompaniment of a ‘son et lumière’ show from the ship’s jarring and the Northern Lights, researchers measured the speed, temperature and salinity of the currents under the ice.

“Even the job of keeping the holes which we used to lower the equipment into the water free from ice was an enormous challenge,” says one crew member. “A 20-cm thick layer of ice could easily form overnight.”

Travel time halved

The Tara expedition showed just how much the North Pole had changed over the previous 100 years. The ice masses brought the ship and the researchers over the Arctic very quickly – twice as fast as when Fridtjof Nansen explored the North Pole in the same way a century ago with the ship Fram.

Nansen let Fram freeze in in the ice, and let the movements of the ice bear the ship from Siberia to the Atlantic.

When the researchers on Tara compared to two expeditions, they noted that Tara took just one year to cover the part of Fram’s route that took two years a century ago.

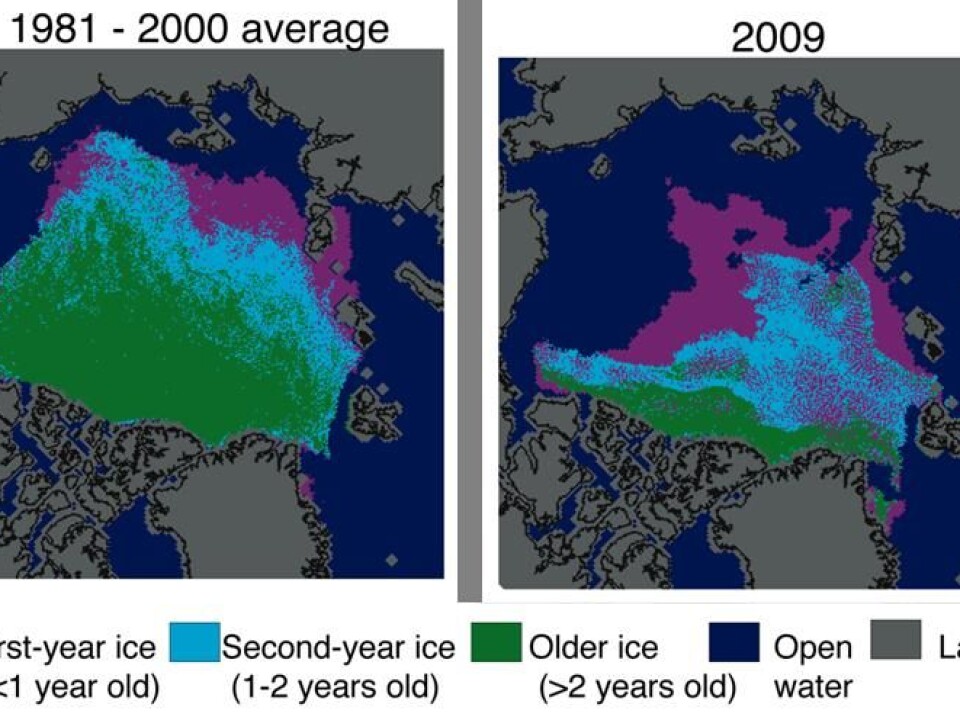

Younger ice

In the ATP project, Gascard and his group build on the data and experiences gained from the Tara expedition.

Now it is obvious that much thinner sea ice is one of the reasons why the Arctic ice moves more quickly.

The researchers have also revealed that the thin ice means that even small seasonal variations in cloud cover or summer temperatures result in extreme variations in the expanse of the sea ice.

The sea ice is simply becoming younger and younger. The old ice – which has been formed over several years – disappears and is being replaced by ice that accrues every year and then melts away.

Glacial algae can’t adapt

The changes in the dynamics and thickness of the ice have enormous impact on both the oceanographic and the biological conditions in the Arctic. Among other things, the changes affect the glacial algae, which adhere to the underside of the ice and are the first link in the Arctic food chain.

The results of the ATP project show that the changes in the Arctic now occur so quickly that the glacial algae and other biological components of the Arctic ecosystem cannot adapt to the new ice and temperature conditions before new changes occur.

--------------------------------------------------

Read this article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Michael de Laine