Cleaning air the natural way

A new air purification unit requires little energy in removing toxic gasses, dust and bacteria, much the way air is cleansed in the atmosphere. The new invention is out of the test lab and now cleaning industrial emissions.

Metal sections have been mounted on the roof of the company Jysk Miljørens in Aarhus, Danmark which literally are making the owners breathe easier.

Until now the company’s neighbours have been protesting the big stink it made. The firm recycles oil from the water in ballast tanks of ships and the process noticeably fouled the air, despite a high chimney. Complaints led to threats of closing the plant down.

But the stench is now history. The metal crates contain the first commercial unit for a new type of air purifier developed by the chemist Matthew Johnson at the University of Copenhagen.

Several advantages

Variations of the purifier can be put to use cleaning emissions and recycling polluted air indoors ‒ in factories as well as homes.

The purifier has several advantages. A major one is that it uses little energy. By recycling indoor air it also saves energy that would be lost in warming up outdoor air in winter.

Certain factories can avoid building tall chimneys to disperse polluted discharges high above the heads of immediate neighbours.

Death zone

The new technology was first presented to the public in the autumn of 2010. Johnson has spent the last two years on the perilous path from the laboratory to the market and industrial use.

In getting there, the researcher had to pass what he calls the “death zone”. This is the zone between labs and markets, where so many great ideas perish before becoming viable products.

“We crossed the death zone with a prototype. I bought a shipping container with a little funding from the industrial development firm Copenhagen Cleantech Cluster,” says Johnson.

As in the atmosphere

And what did Matthew Johnson place in the container? A unit that mimics the air cleaning processes which naturally occurs high in the atmosphere.

In the atmosphere, gasses are heated by the sun and they float to higher air strata. At lofty altitudes they react with ozone and create tiny particles that wash away with precipitation.

Much of that, plus a little more, is what goes on in what Johnson calls an atmospheric photochemical accelerator.

Ozone

At one end dirty air is sucked in. It can contain toxic gasses, dust, smoke, fungal spores, bacteria and viruses, i.e. every health hazard that needs to be removed from the air before it can be safely breathed.

Ozone is first added to the foul air. Ozone kills microorganisms like bacteria and viruses and reacts with certain offensive smelling organic compounds. Ozone purifiers have been on the market doing this job for some time.

But ozone is a poisonous gas. It’s removed in the photochemical accelerator before the air is released from this chamber.

Efficient killer

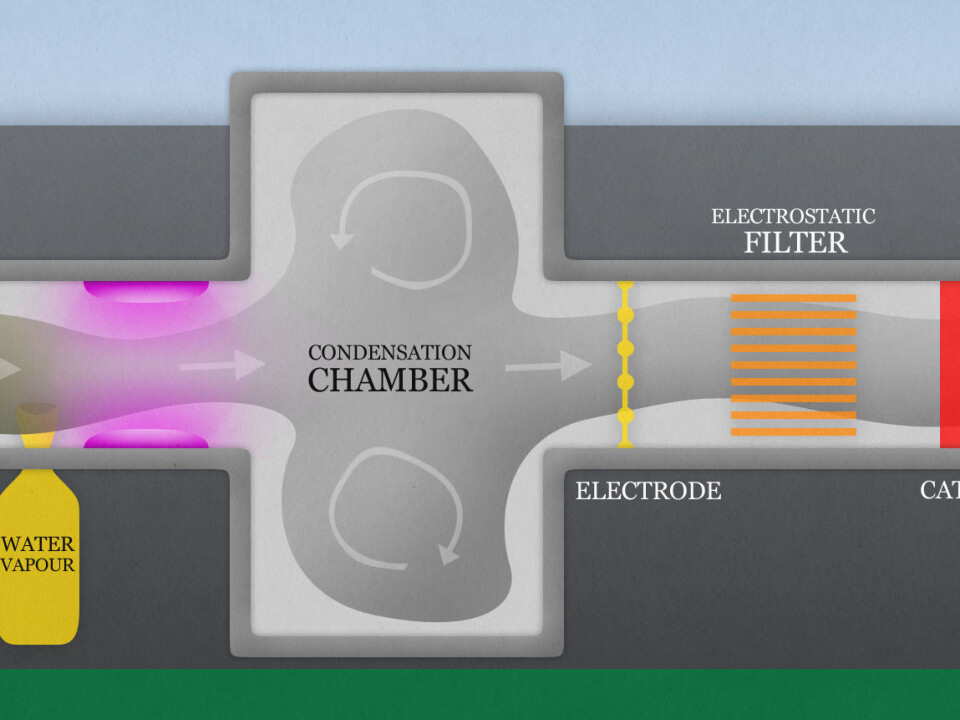

After ozone has killed pathogens and removed bad smells, the suspended residue is collected as specks of dust and water vapour is added to form an aerosol suspension. This aerosol of compound particles and vapour condenses into tiny droplets.

It’s the same process as when clouds form in the atmosphere.

Then the air is irradiated with ultraviolet rays. These UV rays have shorter wavelengths than the solar rays that tan or burn our skin outdoors.

These kill bacteria too. Any microorganisms that survived the ozone shower encounter a deadly challenge here.

However, the UV rays escalate the attack with another function. They react with ozone and water to form bactericidal molecules, hydroxyls.

Anything that survives ozone and strong ultraviolet light will call it quits when it comes in contact with these hydroxyls.

Cloud chamber

After this initial microbiological death trap the dirty air continues to another large chamber. It is given time to circulate here while more and more toxic gasses react with ozone and hydroxyls and attach to aerosol droplets of ammoniac and water.

This is much the same as what occurs in the atmosphere when water vapour collects into raindrops around tiny particles and thus cleans the air.

But raindrops fall to the ground carrying pollutants back down to us with them. The photochemical accelerator has to do better than that.

Given a charge

The dirty fog continues past a powerful electrode and the droplets and particles are given a charge.

This electrical charge is fateful. Soon afterwards the polluted droplets are drawn into metal plates with an opposite charge. It’s an electrostatic filter. The impurities are condensed here and removed.

An electrostatic filter has a large advantage on ordinary filters, such as charcoal filters. It lets air pass through much more freely. It doesn’t require powerful fans to press air through and thus saves more energy.

The air is now cleansed and nearly ready to be released at the opposite end. But first it passes through a catalyst which starts chemical reactions that remove any residual poisonous ozone.

It worked

Testing this principle in a lab is one thing. Getting it to work in the chaotic real world is another.

Matthew Johnson took the container with his purification system to a firm that was struggling to meet stringent emissions standards.

The company demanded anonymity and the tests were done in secret, according to Johnson.

Johnson also wanted to be sure the purifier worked before broadcasting news of the tests.

“We cut a hole in their factory chimney and led the polluted air through the container. I could demonstrate to them that all the pollution had been removed from the airflow,” says Johnson.

First sale

The experiment was a success. The photochemical accelerator was on its way out of the death zone. A group of investors led by the Danish firm Infuser had faith in the invention.

In June 2012 they signed a contract with the University of Copenhagen and in July the first unit was sold to Jysk Miljøindustri.

“In November the first commercial unit was mounted on the recirculation plant in Aarhus and we plan to rebuild the container for new demonstrations of the purifier,” says Matthew Johnson.

---------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling